Remember a time when you felt deep disappointment in how a leader acted. Perhaps they made a decision that valued efficiency over humanity. Maybe they protected themself instead of staying true to the shared purpose of your work together.

Consider a time when you made a choice that went against your values. Perhaps you were pressured by the systems and people around you to rationalize the decision. Perhaps you didn’t know what else to do, you felt afraid or isolated or alone. Perhaps you felt stuck and there was no “good” answer.

When people with power, authority, and choice take action that betrays the purpose or ethic that they espouse, it can cause a deep moral wound for them and for those who work with them. This wound is often called, moral injury. In institutions, organizations, and systems that are organized based on shared purpose and values (most are), there is a particular risk in leadership for this kind of moral betrayal and the fragmentation, mistrust, and misalignment that can result from it. This risk is heightened further in organizations with a shared purpose of service, justice, or healing.

Moral injury is a term popularized in post-Vietnam America by Dr. Jonathan Shay and others who saw the impact of war on the moral fiber of soldiers’ sense of selfhood as they returned home. I believe it is an important concept to understand in 2021 as our global society contends with “re-entry” from COVID-19 pandemic lockdown alongside a year of global reckoning with issues of racial and economic injustice and inequity.

I appreciate the definition of the concept that the Shay Moral Injury Center at Volunteers of America uses on their website as it encompasses the many nuances of circumstances and experiences in times of crisis that can cause moral injury:

“Moral injury is the suffering people experience when we are in high stakes situations, things go wrong, and harm results that challenges our deepest moral codes and ability to trust in others or ourselves. The harm may be something we did, something we witnessed, or something that was done to us. It results in moral emotions such as shame, guilt, self-condemnation, outrage, and sorrow.”

Moral injury involves a moral judgement about what we ourselves have done, what we have witnessed, or what has been done to us. As morality and values are so often culturally and communally shared, moral injury is most often experienced in relationship with others, in connection to our work, in community, or in society at large.

Why do leaders of social change need to know about and learn to navigate moral injury?

Our healthcare, government, and social change organizations are all fundamentally built upon a moral contract with staff and society. There is a set of values that the institution or organization commits to upholding. People join organizations with an expectation that the purpose and values they believe in will be upheld. What is the moral contract that your organization promotes? What are people expecting to be part of and see from your organization as it relates to purpose, values, and impact?

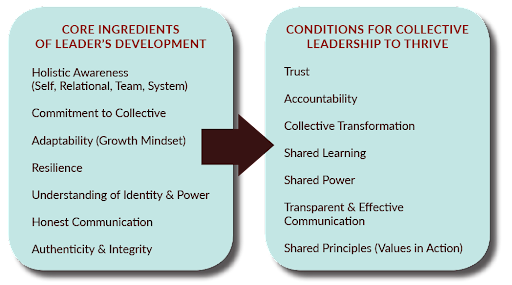

More often than not, our purpose and values are both aspirational and practical. We will not always live up to our values. We will have to make hard decisions and discern compromises at times. Inevitably things will go wrong, mistakes will be made, and harm will occur in the pursuit of social change or social service. BUT how do we make sure that we don’t use the aspirational nature of our purpose or the inevitably of mistakes to lead us into lack of accountability to the collective moral agreement that engages people in our work? What are the practices, rituals, and ways of leading that can support us all in tending to our purpose and values both when it is relatively easy and also when it is incredibly hard?

On their podcast, Finding Our Way, Prentis Hemphill recently asked, “What do we do when the people and institutions in which we’ve given trust fail us? What opportunities are presented in rupture? And in these times, what can we choose to embody?” These are the questions of leadership for social change right now.

How does moral injury manifest in organizations?

Below I’ve highlighted some (not all) of the most common tendencies and markers that I’ve seen in organizations where values-based wounds have not been well tended to or transformed. They often show up together or feed each other. None of these tendencies exists in a silo or in only one person: they are experienced in context and experienced in the collective.

Reactive environment

People and groups are emotionally and spiritually ungrounded, quick to react from a place of preserving one’s personal sense of security. Psychiatrist D.L Nathanson published what he calls the compass of shame to describe four common reactions to shame: withdraw, avoid, attack self, and attack others. We are all predisposed to some or all of these reactions as ways of trying to keep ourselves safe. Sometimes organizational environments that don’t tend to their moral wounds begin to be built upon a foundation of these compass points, making any attempt to find center not only dizzy-ing but also deeply threatening and counter-cultural within the institutional setting.

Persistent mistrust

People don’t trust themselves, others, or the system. There are often very good reasons for mistrust, and yet when it becomes a chronic mindset, it can get in the way of connection and impact. Mistrust reveals some kind of relational fracture. These fractures may exist at multiple levels within the team and organization: systemic, cultural, interpersonal, and personal. When mistrust is ignored over time, the fractures will likely deepen, making them much more difficult to heal and transform without rupture.

Culture of blame

People are quick to blame, to find the person, place, or thing that is wrong. Rather than conversations about learning, values, decision-making, and shared purpose, you might hear a drive to simple stories of problems/conflicts and who or what caused them. Whether or not the blame is acted upon with dismissals doesn’t actually matter as much as how it is felt within the organization and team. With culture of blame present, often hierarchies become rigid, agency is regularly stripped from folks, and people interact more fearfully, hesitating to speak, act, or do anything other than the basic level requirements of their job. In a culture of blame, there is often very little systemic tolerance for mistakes or failure and yet a lot of denial of failures at the highest levels of leadership.

Chronic Hopelessness

People are quick to feel inadequate, helpless, overwhelmed by the needs and demands of the work. Sometimes this manifests in a degree of checking-out, giving up on the bigger changes needed, or turning away from the shared purpose. These are all super normal responses when feeling despair or sorrow or hurt. When these become ingrained in organizational culture, however, there can be a cynicism and disengagement that can manifest related to change initiatives, learning, and evolution in the organizational setting. You might hear things like, “what difference will it make” or “it won’t change” or “the problems are bigger than this.” In organizations with this kind of energy present, there can be a sense of stuck-in-place-ness.

When we notice these patterns are present in ourselves and others, I often invite clients to consider the practice of turning to inquiry with tender curiosity:

- “Where is the wound?” “Where are the wounds?”

- “How might I/we approach this situation with care and compassion?”

- “What mission, purpose, or values might need to be ritually recovered or claimed?”

How do I recognize moral injury in myself or others?

The patterns of interaction listed above may seem very familiar and recognizable. Those patterns often spring forth from emotions: their source material is in our emotional bodies. As such, working with recognizing, allowing and investigating our emotions can be a helpful in road to understanding where we are carrying values-based betrayal or wounding. In working with clients, I am particularly attuned to making space for the often difficult emotions that show up with moral injury. As you read this list below, consider how we might make room for these emotions to be present, to speak their wisdom, and to offer insight that opens pathways to healing.

Rage: When anger is driving, how can we get curious about moral wounds?

Anger and rage are beautiful, important emotions. They often arise from self-compassion and self-protection, offering what is often a momentary reprieve from the despair that can be experienced in suffering. When anger becomes a destructive or chronic bypass of the felt experience of what hurts us, however, it can actually work against healing by distancing us from self-compassion.

Guilt: When guilt is overwhelming, how can we get curious moral wounds?

Guilt can be a feeling that serves us well in identifying beliefs and behaviors that we would like to change in order to live in better alignment with our values or who we know ourselves to be. Fundamentally, guilt invites us to grapple with essential questions about why bad things happen to some and not others, about why inequities and injustices persist, about how we want to live in a world where people can harm each other, and about how we respond knowing we enjoy some privileges that others do not? And when guilt overwhelms, it can cause us to freeze in the face of these questions, to flee from the emotional upheaval or existential rupture of bearing witness to the truth of the answers that emerge, and to fight what’s needed for change.

Shame: When shame is persistent, how can we get curious moral wounds?

Some degree of shame is a healthy experience for society. Experiencing some self-consciousness and self-evaluation when we betray values we believe in is important for us as interdependent, social beings. And yet toxic shame is incredibly dangerous for our health, relationships, and systems. Toxic shame tells the story that something inherently, persistently, and unendingly wrong with who we are. It is often exacerbated by behaviors that seek to temporarily discharge the toxic shame onto those with the least power, authority, and choice.

Despair: When despair is lingering, how can we get curious moral wounds?

Despair is an important feeling to experience as living beings who will inevitably encounter loss. Tapping into the depths of sorrow that can show up when we experience the vulnerability of life or understand the scope of pain in the world around us is not something to try to rid ourselves of entirely. But when emotions like despair gets stuck, floods us, or pushes out space for other emotions, there may be wounds that we are not aware of or not tending to with compassion. This kind of chronic despair in leadership can show up as hopelessness, lack of inspiration or motivation or creativity, isolation, negativity, and resistance to change.

When we feel that rage, guilt, shame, and despair are present in ourselves and others, how can we build awareness of the feelings, allow space for the feelings, and turn to compassionate inquiry:

- “Where is the wound?” “Where are the wounds?”

- “How might I/we approach this situation with care and compassion?”

- “What mission, purpose, or values might need to be ritually recovered or claimed?”

[[For resources and practices to support you in reclaiming and living into your values, check out

the Rootwise Hub.]]